Climbing grades explained

Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of climbing grades. One of the more bamboozling aspects of the sport, the different grade scales can at first appear confusing, difficult, and sometimes just plain unhelpful. However, once you start to understand them, you’ll discover that this jumble of letters and numbers contains a wealth of invaluable information.

How do climbs get their grades?

One thing to make clear is that all grades are subjective. Every single climb has been given a grade by a person, and people do tend to struggle to agree on things. There’s a whole host of variables that can make two routes of the same grade feel completely different - rock type; steepness; ambient temperature; how tall/long-limbed/awake the climber is. The important thing is not to despair if something that you consider an ‘easy’ grade is proving anything but. All grades are subjective.

When someone first climbs a line, they suggest an appropriate grade. This won’t usually make it into a guidebook until a few more people have tried it, and reached a consensus about the difficulty. It’s not uncommon for grades to change - there’s a number of routes that have been either upgraded or downgraded over the years., sometimes by several levels! Generally you’ll find that the most reliably accurate grades are on popular lines that have been climbed a lot.

Roped climbing

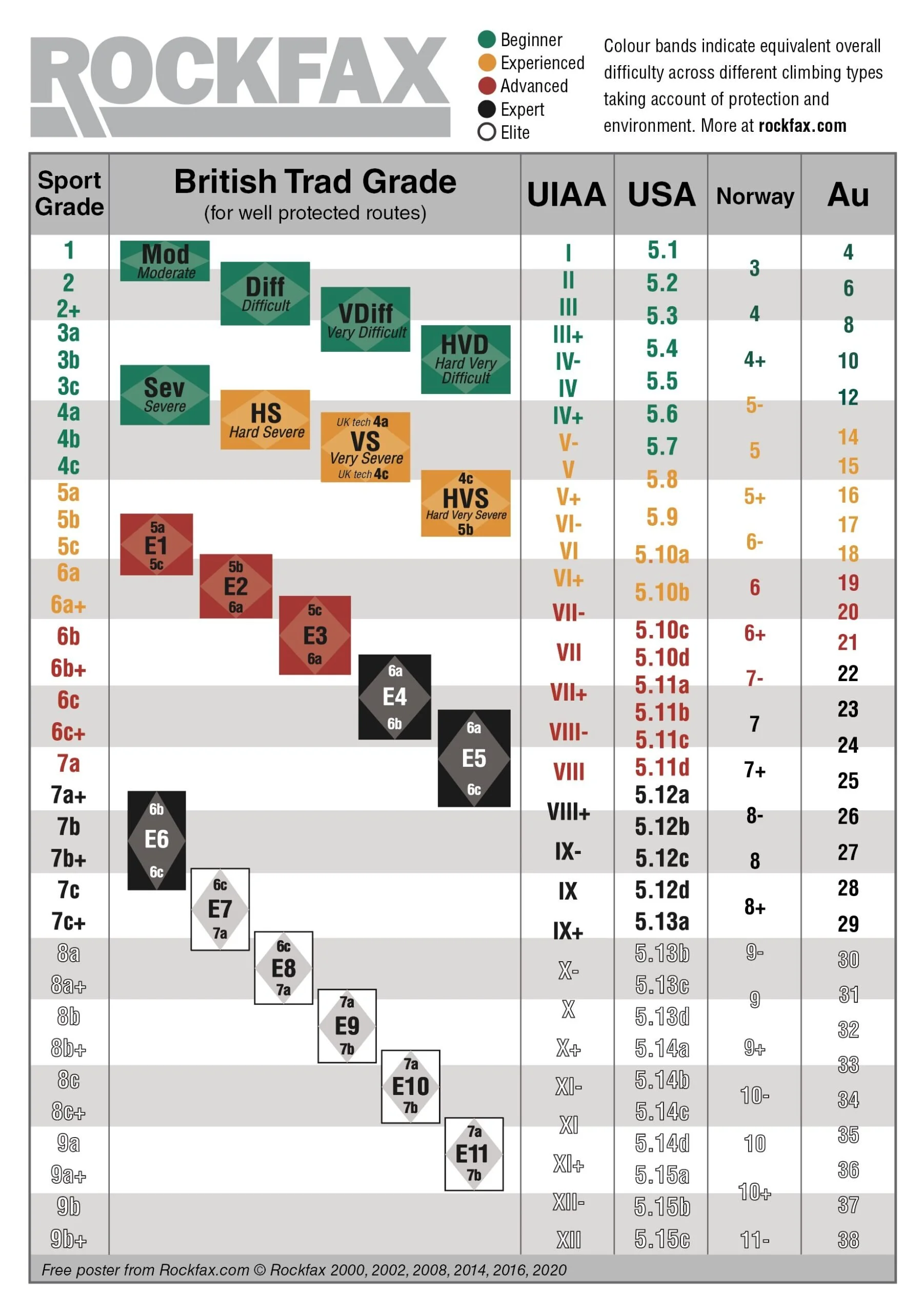

As roped climbing evolved in separate countries across the world, so different grade systems appeared, most of which are frustratingly difficult to compare. This table contains just a few of the different roped climbing grading scales; for simplicity’s sake, we’ll stick to the main ones! In the UK, you’ll find the French sport grades (left column) and British trad grades.

A handy table as an overview, but bear in mind that the different grade scales don’t really compare well!

French sport grades

In the UK and most of continental Europe, you’ll find the French scale in climbing walls and outdoor sport. Originating in France (funnily enough!), the number refers to the overall difficulty of the line - simply, the higher the number, the harder the route. Difficulty can increase for a number of reasons - steeper angle, smaller or more spaced out holds. Finer gradations start to creep in once you hit the 6s, but in general this is a pretty simple system.

British trad grades

Strap in folks, this one is complicated! Only used in the UK, this scale is designed to describe not only the difficulty of the climb itself, but also the protection available. Grades come in two parts:

Adjectival grade (the letters)

Tech grade (the numbers)

Adjectival Grade

This is the overall grade; primarily, it describes the availability and quality of protection - lower grade routes will generally have solid, plentiful gear, whereas on higher grade routes protection tends to be sparser and not so reliable. The adjectival grade also covers the steepness, exposure, ease of access, rock quality and the consequences of a fall, as well as general difficulty.

The list of grades, from easiest to hardest, is as follows (brace yourself!):

Mod (Moderate)

Diff (Difficult)

VDiff (Very Difficult)

HVD (Hard Very Difficult)

S (Severe)

HS (Hard Severe)

VS (Very Severe)

HVS (Hard Very Severe)

E (Extreme)

XS (Extremely Severe)

Well done for making it through! The first thing to point out is that this system has evolved over the best part of a century, which explains the rather kooky nomenclature. When the first Mods and Diffs were recorded, folks were soloing up these routes in leather boots with a hemp rope tied around their middle, so the consequences of a fall would have been much more serious than today. In consequence, what would have been considered difficult and dangerous back then is now, with the benefit of modern technology and techniques, relatively safe and easy. Mod through to Severe are considered beginner routes, HS to HVS intermediate, and the Extreme grades are for more advanced climbers.

The Extreme moniker started to appear in the late 50s/early 60s, and has now evolved into an open-ended grade, from E1 all the way up to E11 (at time of writing). XS is used to describe routes that are trying really hard to fall down, where the poor quality of the rock is the main objective danger. Best avoided!

Tech grade

This tells you how tricky the hardest move/s will be on the route. Although it would be oh so simple if the grades were equivalent to French sport, the two systems evolved separately, and remain stubbornly non-matching. The only given is that British trad tech grades are harder than the French - a British trad 5a will be significantly more difficult than a French sport 5a. Tech grades generally start to appear from about Severe onwards.

Fine tuning

Combining the adjectival and tech grades gives us a really good idea of the overall nature of the route. Average pairings are as follows:

S 4a

HS 4b

VS 4c

HVS 5a

E1 5b

etc

However, each adjectival grade has a range of tech grades that can apply, and reading the two together gives us an idea about protection on the route. If the tech grade is higher, it’s a fairly safe bet that the protection will be better than normal. So if you come across a route that’s say, E1 6a, there will be a hard move or two, but you should be able to place loads of gear.

If the tech grade is lower, then you’d expect the protection to be poor. A good example is a route called California Arete in the Dinorwig slate quarry, N Wales. It gets the grade E1 4c, and consists of a 46m single pitch with only one, fairly pants, piece of gear. Although the climbing is relatively easy, a fall from anywhere would be very serious, hence the higher adjectival grade.

Fun Fact

In North Wales you will find the grades VS, for Vegetably Severe, and HVD, for Hard Very Dirty. We’re not rushing to climb those any time soon…

UIAA grades

Used in Germany, Eastern Europe and the Dolomites, this scale usually applies to bolted sport routes. The very low grades are for scrambles. UIAA stands for Union Internationale des Associations d'Alpinisme, but the scale isn’t used in France. Go figure…

USA grades

The Yosemite Decimal System, used in the States, describes both trad and sport routes, and has some similarities with the British trad scale. The number at the start is the class, and ranges from 1-5. Classes 1-4 cover hikes and scrambles, and when you hit 5 you are into rock climbing territory. Sub-classes kick in here, and range from 5.0 to 5.15 at time of writing, with finer gradations appearing at 5.10 (5.10a, 5.10b, 5.10c etc).

Sometimes you will see an extra suffix, describing the protection, which mirrors the American film rating system:

PG (parental guidance): protection may be spaced out

R (restricted): falling will likely result in injury

R/X (restricted/adult audience): falling will likely result in serious injury or even death

X (adult audience): falling will likely be fatal

Norway

Similar to the UIAA scale, but using numbers instead of roman numerals. This system applies to trad and sport, and, as the grade bands are fairly wide, routes of the same grade can vary greatly in difficulty.

Australian/New Zealand

The Ewbank system, used in the Antipodes and South Africa, was developed by John Ewbank, a British-born climber who emigrated to Australia in the 1960s. Grades range from 1-37 (at time of writing), the easiest grades applying to scrambles. Ewbank rejected the concept of separate grades for danger and difficulty, preferring to keep things simple and give each climb one overall number. Instead, any extra danger or difficult moves are described in the guidebook route descriptions - a canny move, as he had written most of them!

Bouldering

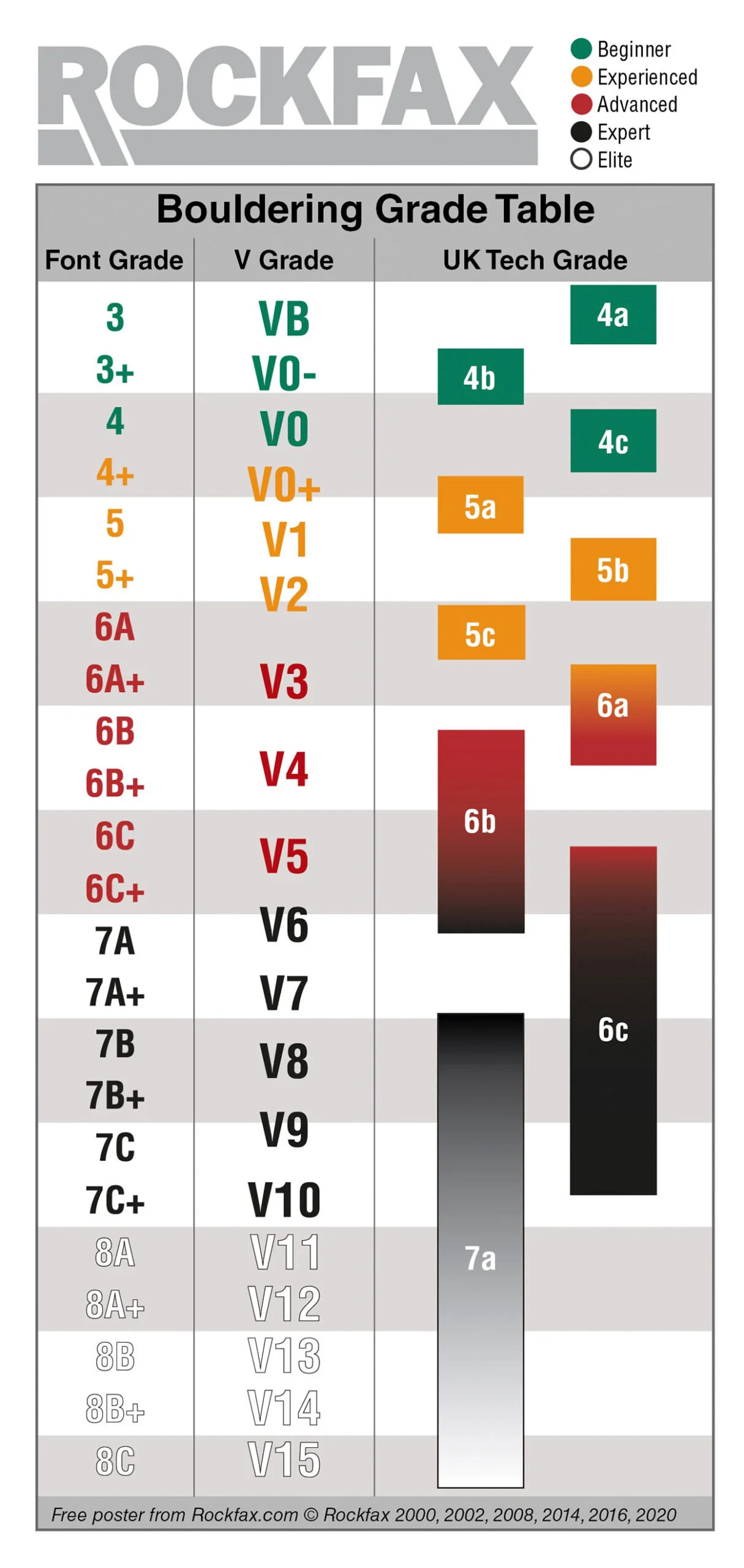

You’ll be glad to know that the bouldering is a much simpler world - there are only really two scales that you’re likely to come across: Font grades and V grades. The UK trad tech grade was used in the past to describe boulder problems, but this is rare nowadays.

Font grade

This scale is used outdoors and in climbing walls across the UK and Europe, and originated in Fontainebleau, a vast collection of sandstone boulders just south of Paris. Arguably, this is where bouldering began, and the open-ended grade scale that was developed ranges from 1A to 9A (at time of writing). Whilst it may appear similar to the French sport grade, the two are not the same - Font grades are much harder - so to distinguish between the two, Font grades have upper case letters (8A), and sport grades lower case (8a).

V grades

The V scale, or Hueco scale, was devised by legendary boulderer John Sherman at Hueco Tanks, Texas, in the 1990s, and is found across the States, as well as much of the UK. Also an open-ended scale, the range spans from VB (where B stands for ‘basic’, or ‘beginner’) to V17 (at time of writing). The V stands for ‘Vermin’, Sherman’s nickname.